THE INFANTRY

I left the infantry section on the Spanish army until last part as it's the most complicated to explain. The Tercios of Spain, both those of the native Spanish and the other nations, were the best part of the Army. Indeed the best of them were regarded as the best infantry in Europe until after Rocroi (1643). The Infantry consisted of the Spanish Tercios, The Tercios of the Nations (drawn from other Hapsburg possessions in Flanders and Italy and lastly mercenary units tercios of Irish, Scottish and English troops and regiments of Germans and Swiss.

The Tercios

Tercios were infantry formations of Hapsburg subjects (Spainish, Walloons, Italians) and volunteers from other countries primarily Ireland. The formations and tactics of the Tercios were emulated by both the Holy Roman Empire and the allied Catholic League until the 1630's. They fought in Flanders in the 80 Years War (aka the Dutch Revolt), in Italy in the War of the Mantuan Succession, in Switzerland, in France, and in Iberia itself against the Portuguese and Catalan rebels as well as in North Africa and of course saw action in the Thirty Years War. During the period I'm covering they went from being the traditional Tercio with the four corner bastions of shot to something more akin to the pike and shot formations recognised from the BCW.

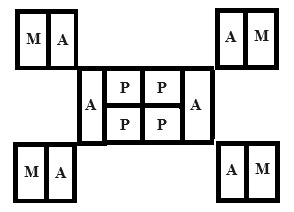

|

| 1. Period illustration of a Tercio showing the four corner Mangas of shot |

The long established view was that they were ultra conservative tactically, and struggled to adapt to the changes brought in by Prince Maurice of Nassau (the Dutch tactical style) or Gustav Adolphus (the Swedish tactical style). Yet at Nordlingen in 1634 the Tercios destroyed a Swedish Army and previously they had done the same to the Dutch. In fact many of the tactical changes brought about by Maurice were already used in whole or in part by the Spanish! The basic story of the evolution of Spanish infantry squadrons (the battlefield tactical formation) is that over time they became smaller, less deep but wider and with an increasing proportion of shot. Of that shot a larger proportion of the shot became armed with muskets. At some point the corner formations of shot (the Mangas) became the wings of shot at either side of the pike. What is less easy to tell is when these changes happened so as to be able to say that at a specific battle the squadron looked and fought in a definite way.

A Tercio at the start of the century had an official strength of 3,000 men, although in reality they usually had less men than this, around 1,500 of all ranks in Spanish and Italian tercios and under 800 in Irish and other volunteer Tercios. The Spanish preference for large infantry formations meant a single Tercio could form a squadron on its own or companies from two or more would be merged together. Writing sometime in the early 1630's Gerat Barry (An Irish volunteer who served in the Spanish Army between 1602 and 1632 retiring with the rank of Captain in the Army of Flanders) states that:

"The 4. formes of squadrones moste acustomed and moste in use,is the square of men, the square of grounde, bastarde square and broade square, which the Spaniarde caule quadra de gente, quadra de tereno, prolongado, y gran frente"

(Gerat Barry - A Discourse of military discipline - published 1634)

Based upon Barry we can be fairly sure what the common formations were during the 1620s and possibly until Nordlingen in 1634 as Barry was writing prior to 1633 (when his text was submitted for official approval!). Barry goes into great detail on the arithmetic required to determine the number of ranks and files to form up in (square roots are a bit of an obsession with military writers in the period) but less on the other aspects of deploying a squadron.

The core of those formation was the central pike block, which throughout the period always had two small wings of Arquebusiers permanently attached, known as 'Garrisons'. To that were added four bodies of shot (The Mangas) which were armed with either arquebus or musket. In the mid 16th Century these formations were around 3,000 men strong as shown below (images of the formations are from Pierre Picouet's web site on the evolution of the Tercio via the Internet Archive). The basic formation seems to have continued in use until at least the early 1620's but with a lower head count.

|

| 2. A 'Field Square' consisting of 2922 men of the mid to late 16th Century |

Other variations on the formation existed as noted by Barry. The extended square sacrificed depth for width to increase frontal firepower while the square of men was deeper than it was wide. Again examples from Pierre Picouet’s now defunct website are below.

|

| 3. 16th and early 17th Century formations |

By the early 1630's we are starting to see a more easily recognisable German style formation with a pike centre and two wings of shot but still with the garrisons of arquebusiers. This may actually have been the most common formation from sometime in the 1620's (see the section on sources below).

|

| 4. Deployment of 1,057 men from the mid 1630's with Pike 10 deep and shot wings 9 deep |

The key thing to note is that arquebus armed shot are still in use in the above formation and this continues until at least the Ordinance of 1685 where a third of the squadron still had them, perhaps because an impoverished Spanish Crown had to make do with the firearms they already had!

Pierre Picouet provides some useful statistics in his book 'The Armies of Philip IV of Spain 1621-1665 (Helion 2019) on the size of battlefield squadrons and the weapons mix being used. I also picked up useful stuff from the Osprey on the Spanish Tercios so other authors (other than Mr Picouet) are available!

This is where it starts to get complicated. Tercios in Flanders, Italy and Iberia were organised in slightly different ways and were of different official sizes to each other in any given year. I have no idea why this was. German mercenaries brought a totally different organisation to the party (see below) and there were several reorganisations across the period. It is possible to ignore this though, as the squadron was the fighting unit not the tercio, but the differences in manpower pools and weapon ratios could have had an impact. Still for wargaming purposes a bit of standardisation can be applied.

The average size of the Infantry and Cavalry squadrons varied by army and date but the following table adapted from Mr Picouet's The Armies of Philip IV of Spain 1621 - 1665 gives an idea of the formation sizes we should be using on the wargames table.

|

| 5. Average squadron sizes at major battles (source Pierre Picouet) |

|

| 6. Weapon splits and rough ratios |

The percentages are from Mr Picouet's work the ratios are my (very) rough approximations based upon those splits. Ordinances are the official instructions for how a tercio should be composed and muster rolls are actual head counts at pay musters. Care has to be taken with the later as there was a tendency to claim pay for dead or deserted soldiers. Muster data for the earlier periods tends to be in line with the ordinance requirements.

German infantry were recruited in the same way as was done in Imperial and Catholic League service, by issuing warrants to military contractors. The basic unit for German formations being the Regiment. These seem to have been organised in the same way as infantry formations of the Catholic League. I take that to mean that until the mid to late 1620's they would be using the same formations as the Spanish (Possibly 'el Prolongado' as they were musket heavy formations) and then changed to the mid 1630's formation shown in image 4. However Daniel S on his Kreigsbusch blog considers that German infantry (both Leaguist and Imperial) may have abandoned Spanish formations earlier in the century. Giorgio Basta's military manuals recommend formations 10 deep as early as 1610 which is different to Spanish doctrine, I would use 12 ranks as that is the best I can do with the 2mm blocks I use. At Lutzen (1632) Wallenstein deployed his German infantry in Battalia of 1,000 men deploying them 10 ranks deep (some sources state 7 ranks) which was probably also the formation used by mercenary formations.. As with the Tercios the actual numbers in field formations slowly reduced and formations became wider and shallower. Between 1630-33 average size was 1,923 men falling to 1,500 men in 1640 and 851 men by 1643. In the 1620's the split between weapon types was 40% pike, 10% Harquebus and 50% muskets giving a ratio of 2:3 pike to shot overall. In general terms I would go with unit sizes and formations similar to Catholic League and Imperial battalia and with the same weapon splits. For training and experience I should start with Trained and Experienced and adjust upwards or downwards depending on the actual performance of the troops in the battle being refought.

SOURCES

Primary Sources

Giorgio Basta - Il maestro di campo generale...(Venice 1606), and Il governo della cavalleria leggiera (Venice 1612). (OK I will admit my Italian isn't really up to reading the originals so I have relied on translated extracts in secondary sources).

Gerat Barry - A discourse of military discipline - (Brussels 1634). Available through Early English Books Online free version but without illustrations.

Secondary Sources (contemporary)

Period paintings and engravings by contemporary artists (I have counted these as secondary sources as we can't be certain the artists were actually present or how accurate their depiction of fighting formations are. These are all from internet sources. Different artists sometimes portray the same battle with different infantry formations, one must be wrong, but which one?

Pieter Snayers' Paintings. These over a lot of important TYW battles. Although he was not present at them himself, he did use input from those who were and his patrons were military men who may have had an input to the technical details. As a result his paintings are considered to be reasonably accurate. I treat them as giving some indication of army deployments and possible unit formations.

|

| Battle of The White Mountain 1619 by Pieter Snayers - note the infantry formations |

A number of contemporary engravings ( for example those of Matthias Merian The Elder's) . These do not always provide the detail of Snayer's paintings but they give a different view of the formations used. Many are by unknown artists so the accuracy cannot be vouched for.

Secondary Sources (Modern)

The Armies of Philip IV of Spain 1621-1665 - Phillip Picouet - Helion & Company 2019

In the Service of the Emperor, Wallenstein's Army 1625 - 1634 - Laurence Spring Helion & Company 2019

Imperial Armies of the Thirty Years War (1) Infantry & Artillery - Vladimir Brnardic - Osprey

Imperial Armies of the Thirty Years War (2) Cavalry - Vladimir Brnardic - Osprey 2010

Pike and Shot Tactics 1590 - 1660 Keith Roberts - Osprey 2010

Plus various Wikipedia pages and websites on Battles of the Thirty Years Wars too numerous to list (or remember).

Fascinating study of the Tercio and its evolution. I will return to this post as a reference.

ReplyDeleteThanks!

What a fantastic and very useful post. You excelled yourself. I’ve been interested in this period for some time but have never managed to gather together as much info in one place as this. Kudos.

ReplyDelete