Under Gustavus Adolphus the Swedes became the next important battlefield innovators. They further developed the tactics and deployments of the Dutch Army and demonstrated their effectiveness on the Battlefield. That said it is hard to know where to start in describing the evolution and tactics of the Swedes as so much has been written and so many books, websites and blogs cover the topic. Certainly I'm not going to bring anything new to the table. Instead I'm going to concentrate on how to play a Swedish Army for the period.

|

| 1. 1632 portrait of Gustavus Adolphus (reigned 1611 - 1632) |

So why bother at all? Well at Breitenfeld in 1632 the new Swedish tactics destroyed an Imperial Army under Tilly. This has to be something worth looking at to see how it can be replicated on the tabletop. Especially as Tilly was an experienced commander who until that point had (allegedly) never lost a battle.

|

| 2. Breitenfeld 1631. Engraving by Matthaus Merrian, note the deep formations of cuirassiers standing off to shoot from a distance |

At the start of the Seventeenth Century Sweden was not a particularly populous or wealthy kingdom, neither was it in the forefront of military innovation. What it was, though, was involved in a number of territorial and dynastic disputes within Scandinavia, Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The experience gained in these conflicts showed that the Swedish military required modernisation. During the 16th century the Swedish army was based upon volunteers from the peasantry who formed the infantry and cavalry formed from the nobility. Unusually, the infantry were organised into semi-permanent bodies who were maintained in garrisons or billeted. Cavalry came from the nobility as and when required.

Hard lessons were learned in fighting Polish heavy cavalry in the period 1600 - 1629. Swedish cavalry lacked the armour and large breeds of horses needed to create the three quarter armoured horse favoured in the rest of central Europe. Other solutions had to be found to allow any chance of beating Polish heavy horse. Equally the infantry had to be bolstered to provide an effective anti-cavalry defence if the cavalry battle went against the lighter Swedish Horse.

Those solutions were found and the Swedish Army which entered the Thirty Year's War would show itself as capable of standing and beating the best of the Hapsburg's Imperial army. To do this Gustavus Adolphus had turned to both the best of the Dutch system, the writings of the classical age military theorists and added a dash of home grown inventiveness.

Infantry

Theoretically infantry regiments composed of ten companies each of 100 men. The Regiments were divided into two squadrons each of which was intended to be of around 500 officers and men. These were the building blocks of the infantry tactical combat unit the Brigade. In reality some regiments were understrength so only formed one squadron others could form the bulk of a Brigade one their own.

Swedish Infantry was generally well trained and experienced. Any foreign troops taken into Swedish service were trained and equipped to fight in the same formations and use the same tactics as Swedish troops. These units were backed up by mercenaries from Germany and Scotland as well as allied troops from German protestant states. Mercenaries were equipped and fought in the same way as the native Swedish troops, allies in their state's preferred style which was commonly Dutch until the mid 1630's.

The Swedish Brigade

The Swedes were famous for the use of the intricate 'Swedish Brigade' during the period immediately before and during the early years of their involvement in the Thirty Year's War. Yet in reality it was only in use for a relatively short period. The Swedish Brigade initially started life with three squadrons in an arrow head formation (1627-28) changing to four squadrons arranged in a diamond (1628-31) which reverted to three squadrons again (1631-34). Finally the three squadron brigade's formation was simplified, probably sometime prior to Nordlingen, with each squadron consisting of a central block of pikes flanked by two sleeves of musketeers, but still in the arrowhead formation. After Nordlingen the Swedes abandoned the brigade as a combat formation and moved to the German style of tactics (as used in the later stages of the first BCW).

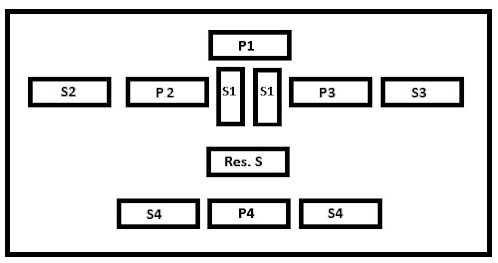

The key to understanding the Swedish Brigade is to realise that the illustrations commonly found in modern books and in Cruso's period manual are only the initial formation. The brigade was not a static entity and changed when fighting to create different brigade combat formations determined by the situation. According to a recent response on TMP by Daniel S, (who I am told is Daniel Staberg) and whose views I place a lot of value upon, there were possibly six basic formations available. I have found details on a couple as shown below. In the following P is a pike block and S a shot block, the number shows which squadron they are drawn from. In each case the top of the image would be facing the enemy.

Each Squadron was theoretically made up of 216 pikemen in 36 files by 6 ranks and 288 musketeers in 48 files by 6 ranks. However, when compared to a three squadron brigade (from Cruso) the average number of musketeers for each squadron is less than this at 208 men, so each squadron has lost 16 musketeers 48 men in total who probably were sent to provide fire support to the horse. Given the obsession with having complete files of six that means 8 files are detached but those can't have been taken equally from each of the three squadrons as clearly dividing 8 files by three squadrons doesn't give a round number of files. So in theory a Swedish squadron had a pike to shot ratio of 1:1.333 so for our purposes close enough to use either 1:1 or 1:1.5 depending on how you want to round the numbers.

|

| 3. The ideal three squadron initial deployment |

The reserve shot block was used to fill gaps in the other musket blocks. Some of each brigade's shot would also be detached to support the cavalry wings.

|

| 4. The ideal four squadron initial deployment |

|

| 5. Late three squadron initial brigade formation circa 1634 |

Next we have to consider what the actual fighting formations were and when they were used.

|

| 6. Three squadron brigade pike forward. |

The pikes forward formation may have been used as both melee (attacking) and defensive formation. Daniel S says that he is aware of a brigade attacking in this formation at Lutzen. Andre Schurger says it was a defensive formation but that there is no evidence for it's use. So I'm going to say its a formation for use when the brigade's flanks are secure and hand to hand combat is immanent particularly against horse. Whether the shot then joined in the fighting would probably depend on circumstances.

|

| 7. Three squadron brigade in an attack posture shot forward |

I see the shot forward variant as a more general purpose attack formation, perhaps where the flanks of the brigade are less secure or where weight of firepower is considered more important. I would expect that after a couple of volleys the pike would move forward through the shot to engage at point of pike.

These are the only formations I have seen images of (Plus a mention of a brigade throwing it's shot forward by 15 paces to form a line ahead of the pike) but I could see how a number of variations could be deployed to meet different eventualities.

So if you have managed to get your head around all of the above, guess what you can pretty much forget all of it! That's because the next issue is that the brigade formations in the manuals are ideal versions and the actual formation strengths and pike to shot ratios could and did vary a good deal from the ideal versions.

According to Andre Schurger's thesis (see below) the infantry brigades at Lutzen had wide variations in pike to shot ratios with some having no pike at all!

|

| 8. Swedish Infantry formations and manpower at Lutzen (1632) after Schurger (2015) |

The above list shows the Infantry present at the battle of Lutzen (1632) and derives from two contemporary documents. It details the units which made up each brigade, the number of companies in those units and the number of musketeers, pikemen and officers in each. How the split between pike and musket was determined I can't tell. I noted that dividing the number of officers by the number of companies gives a total of 12 officers per company in every case which seems perhaps a little too neat. Although only showing a snapshot for one battle it shows how wide the variation from the theoretical organisational plan was in reality. Very few units have an average company size close to the paper establishment of 100 officers and men , which is to be expected after some hard campaigning.

Please note a great deal of the information in this post was drawn from the background sections in the following work:

The archaeology of the Battle of Lützen: an examination of 17th century military material culture. PhD thesis Schürger, André (2015) University of Glasgow

This post has become a bit lengthier than I expected so I'm going to split it into two parts as I did the one on the Spanish. Next up will be a look at the cavalry, artillery and army deployments as well as how to put it all together to create a wargames army with a distinctly Swedish feel to it.

Finally, all the relevant Swedish deployment info in one place, and concisely explained. Thanks for the research and the post. Most informative.

ReplyDeleteI can't help but think that those formations (and the changes from one to the other) would need a lot of training to get right and halfway fast enough for battlefield conditions.

ReplyDeleteWhich is pretty much why the Brigade was abandoned. The quality of soldiers declined and the net gains from having such complex formations didn't outweigh the gains from having soldier proof simple ones.

DeleteElenderil

Thanks for this, great to see a good explanation of how the famous 'Swedish Brigades' actually worked ( in theory at least ). I can quite understand how the methods would have been hard to keep up as continual campaigning wore down the original cohort of well-trained men, so the simpler formation in use by the time of Nordlingen seems entirely sensible, with more mercenaries in the ranks and Gustavus no longer overseeing training etc. I was vaguely aware of the archaeological findings from Lutzen in recent years, I think I probably saw a TV documentary ( possibly German, but sub-titled ) about it on Youtube. I think they had perhaps even managed to tie in Swedish muster rolls with evidence from mass graves on the battlefield, to the point of working out which unit was represented in which burial pit...

ReplyDelete